About the Debate

About the Future of Conservation debate

Although discussions about the aims and methods of conservation probably date back as far as conservation itself, the ‘new conservation’ debate as such was sparked by Kareiva and Marvier’s 2012 article entitled ‘What is conservation science?’.

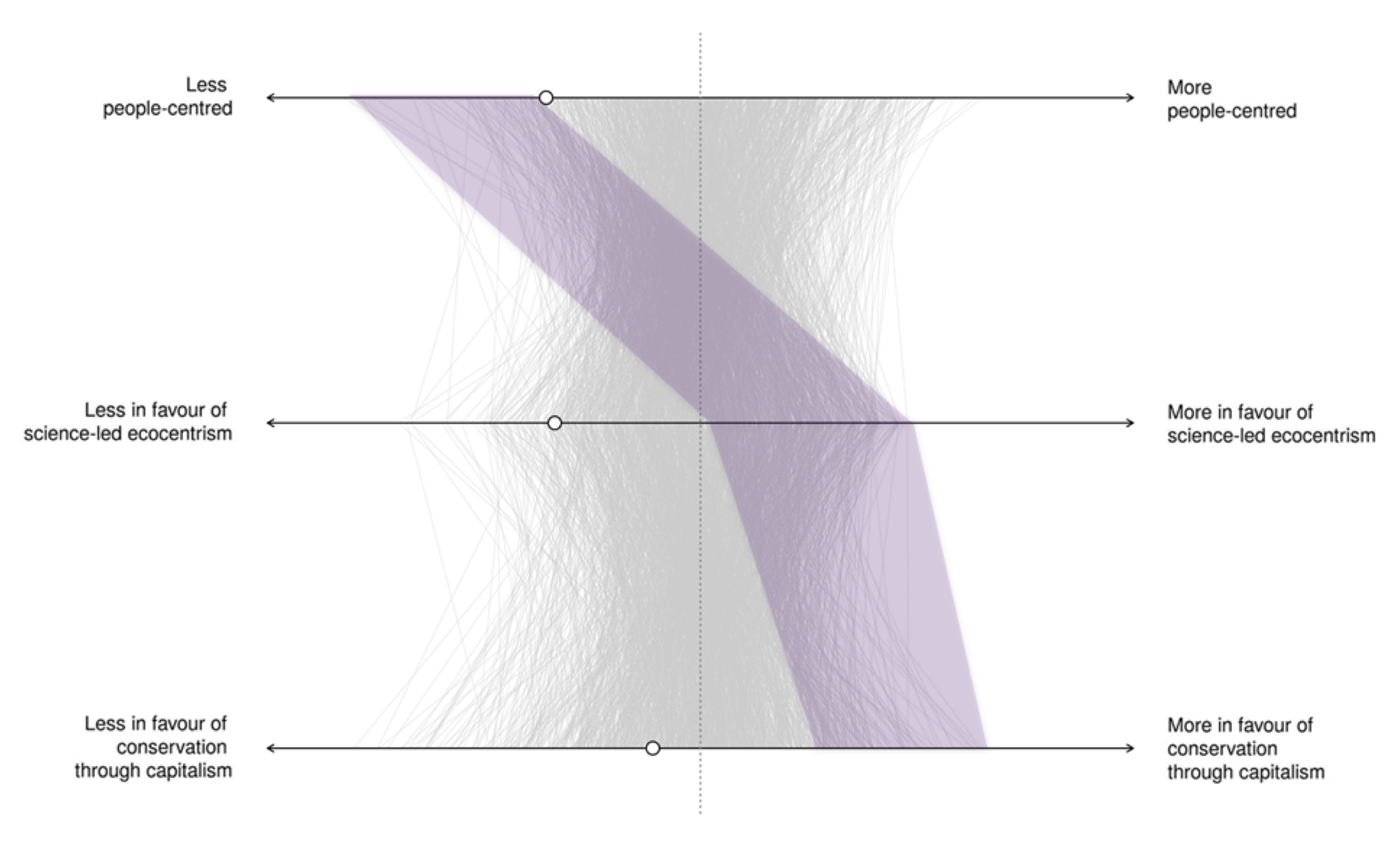

Two prominent positions emerged in this debate, that of Kareiva and Marvier, which they called ‘new conservation’, and a strongly opposed viewpoint that we label ‘traditional conservation’. Our research emerged from our concern that these two positions did not adequately describe the range of views held by conservationists around the world.

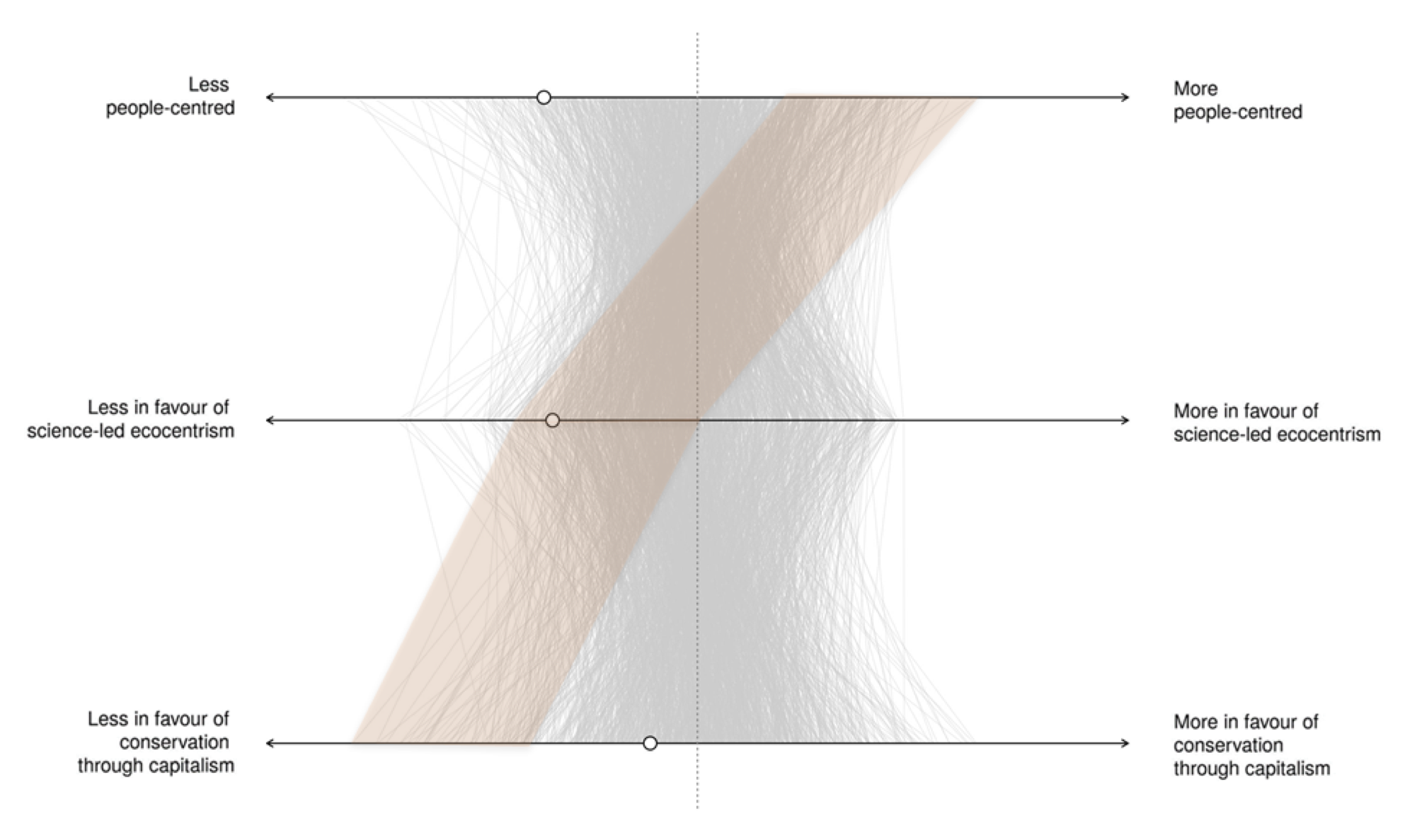

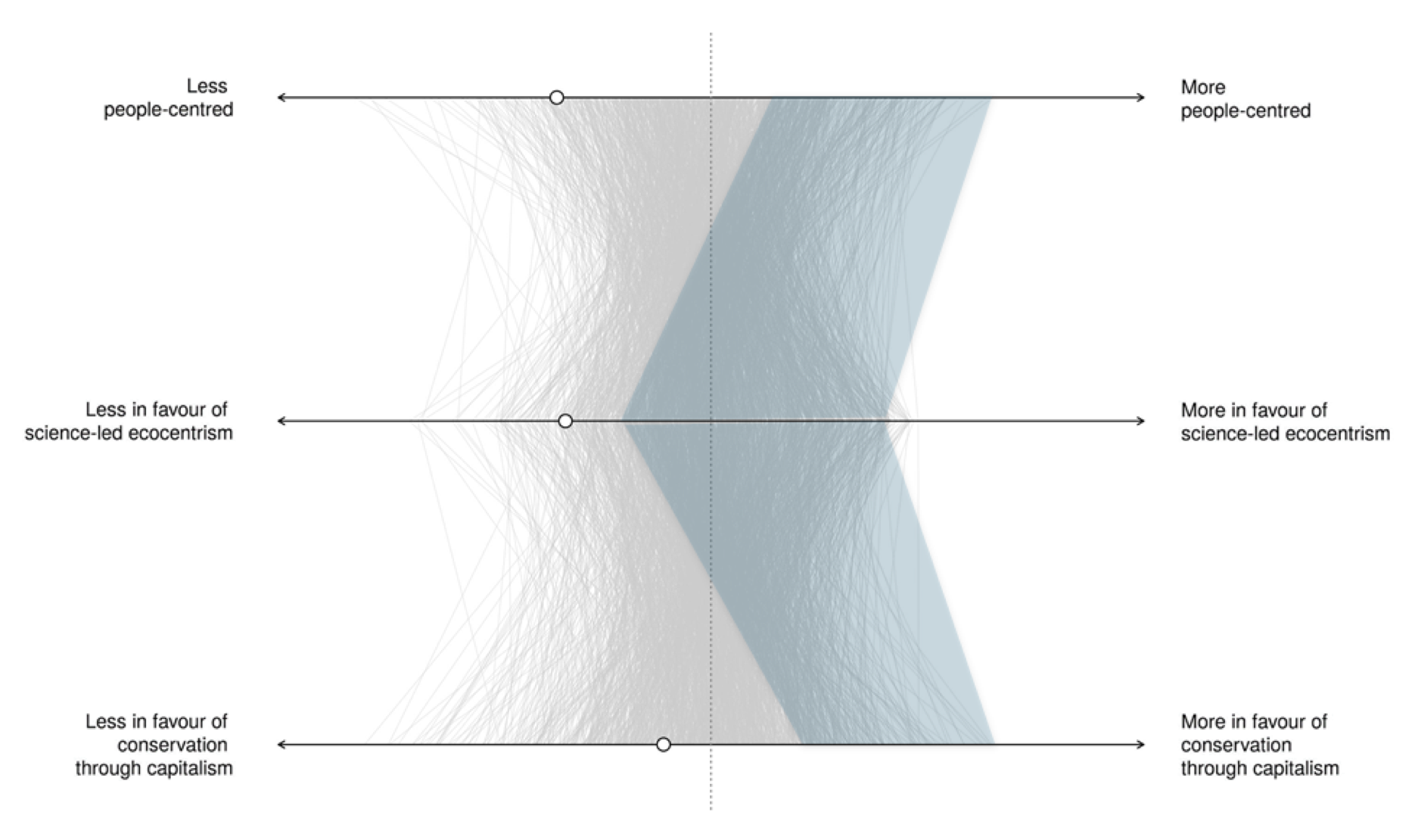

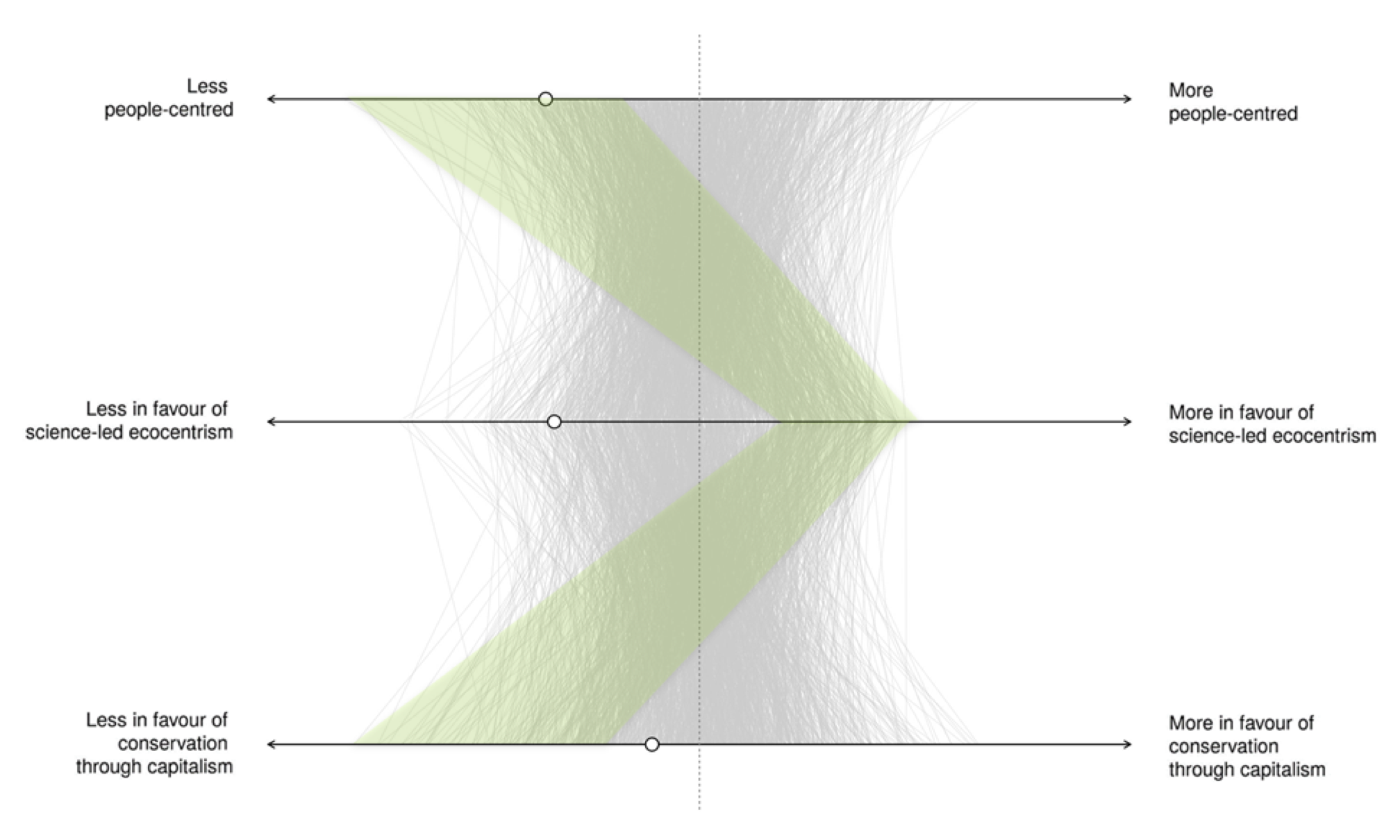

The new and traditional conservation positions can be clearly distinguished by their views on the role of ‘people-centred conservation’ (relating to the role that people should play in conservation), ‘science-led ecocentrism’ (relating to the role of science in the conservation of species and ecosystems), and ‘conservation through capitalism’ (relating to the role of corporations and market based approaches in conservation).

This page describes these positions, as well as two others that have been previously identified in the literature about the ‘new conservation’ debate. Using diagrams, it also shows how these positions relate to the three axes identified by our research. However, our work suggests that many conservationists do not belong to any of these four positions; or they hold different combinations of the views expressed in the literature. We include descriptions of these four positions here for information, but support efforts to move beyond characterising conservationists into separate ‘camps’.

New Conservation

Central to the ‘new conservation’ position is a shift towards viewing conservation as being about protecting nature in order to improve human wellbeing (especially that of the poor), rather than for biodiversity’s own sake (hence the relatively high score on the people-centred conservation axis).

‘New conservationists’ believe that win-win situations in which people benefit from conservation can often be achieved by promoting economic growth and partnering with corporations, corresponding to a high score on the ‘conservation through capitalism’ axis.

Where new conservationists stand on the second dimension, science-led ecocentrism, is harder to say. On the one hand, new conservationists often criticise conservation approaches which mainly focus on protected areas, making their score on this dimension lower than for other positions, such as traditional conservation. Nonetheless, judging by the published literature, new conservation advocates are generally enthusiastic about conservation goals being based on evidence from the natural sciences, potentially making their score on this axis slightly less negative than that of critical social scientists, who often highlight the importance of input from other disciplines.

Although new conservation advocates have been criticised for doing away with nature’s intrinsic value, key authors within the movement have responded by clarifying that their motive is not so much an ethical as a strategic or pragmatic one. In other words, they claim that conservation needs to emphasise nature’s instrumental value to people because this better promotes support for conservation compared to arguments based solely on the rights of species to exist.

Traditional conservation

Traditional conservationists often support the protection of nature for its own sake, often advocating the use of protected areas as the main tool for conservation (hence the high score on the science-led ecocentrism dimension).

This emphasis on nature’s intrinsic value typically leads traditional conservation advocates to score relatively negatively on the people-centred conservation dimension, as key figures, such as Michael Soulé, have claimed that conservation should be distinct from humanitarianism, and that, whilst the alleviation of poverty is of general moral concern, this should not become the primary focus of conservation organisations.

Traditional conservationists tend to also be critical of markets and economic growth as tools for conservation. This is because they believe that by embracing markets, we run the risk of ‘selling out nature’ by neglecting species that may be considered to be of little economic value. What’s more, economic growth itself is seen as a major driver of threats to biodiversity.

Market ecocentrism

Perhaps one example of ‘market ecocentrism’ is the recent Nature Needs Half movement (as well as the closely related Half-Earth movement). In his book entitled ‘Half-Earth’, biologist Edward O. Wilson uses scientific arguments about biogeography to advocate the setting aside of half of the world’s area as ‘inviolable nature reserves’. The motivation for these reserves would predominantly be to protect species and ecosystems for their own sakes; hence the positive score on the science-led ecocentrism dimension, and the relatively negative score on the people-centred conservation dimension. Aware that this ambitious target would require a drastic decrease in per capita environmental footprint worldwide, Wilson supports free markets as a means to favour those products which generate the maximum profit for the minimum energy and resource consumption (hence the positive score on the conservation through capitalism dimension).

However, Wilson’s pro-markets view seems to be more to do with ensuring that humanity can flourish on only 50% of the Earth’s surface rather than as a tool for carrying out conservation: that is, the pro-market strategy would be used to buffer the ‘human’ half of the Earth against the need to exploit the ‘natural’ half, rather than as a means to create economic value from protecting the ‘natural’ half.

Other instances of market ecocentrism include strategies in which market tools, such as ecotourism and ‘willingness to pay’ approaches are used to generate revenue to fund the creation and maintenance of protected areas.

Bibliography

New Conservation:

- “Conservation in the Anthropocene -- Beyond Solitude and Fragility.” Accessed February 24, 2015. http://thebreakthrough.org/index.php/journal/past-issues/issue-2/conservation-in-the-anthropocene.

- Kareiva, Peter, and Michelle Marvier. “What Is Conservation Science?” BioScience 62, no. 11 (November 1, 2012): 962–69. doi:10.1525/bio.2012.62.11.5.

- Kareiva, Peter. “New Conservation: Setting the Record Straight and Finding Common Ground.” Conservation Biology 28, no. 3 (June 1, 2014): 634–36. doi:10.1111/cobi.12295.

- Levin, Phillip S. “New Conservation for the Anthropocene Ocean.” Conservation Letters 7, no. 4 (July 1, 2014): 339–40. doi:10.1111/conl.12108.

- Marris, Emma. “‘New Conservation’ Is an Expansion of Approaches, Not an Ethical Orientation.” Animal Conservation 17, no. 6 (December 1, 2014): 516–17. doi:10.1111/acv.12129.

- Marvier, Michelle, and Peter Kareiva. “The Evidence and Values Underlying ‘New Conservation’.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 29, no. 3 (January 3, 2014): 131–32. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2014.01.005.

Traditional conservation:

- Soulé, Michael “What is conservation biology?” Bioscience 35, no. 11 (December, 1985): 727-734. Doi: 10.1111/cobi.12147

- Greenwald, Noah, Dominick A. Dellasala, and John W. Terborgh. “Nothing New in Kareiva and Marvier.” BioScience 63, no. 4 (April 1, 2013): 241–241. Doi:10.1525/bio.2013.63.4.18.

- Noss, Reed, Nash, Roderick, Paquet, Paul, and Michael Soulé. “Humanity’s Domination of Nature is Part of the Problem: A Response to Kareiva and Marvier.” BioScience 63, no. 4 (April 1, 2013): 241–42. Doi:10.1525/bio.2013.63.4.19.

- McCauley, Douglas J.. “Selling out on Nature”. Nature 443 (September 7, 2006): 27-28. DOI: 10.1038/443027a.

- Wuerthner, Geroge, Crist, Eileen, and Tom Butler (eds.). Keeping the Wild: Against the Domestication of Earth. Island Press. Doi: 10.5822/978-1-61091-559-5

- Miller, B., M.E. Soulé, and J. Terborgh. “’New Conservation’ or Surrender to Development?” Animal Conservation 17, no.6 (December 1, 2014): 509-15. Doi: 10.1111/acv.12127

Critical social science:

- Büscher, Bram, Sullivan, Sian, Neves, Katja, Igoe, Jim and Dan Brockington. “Towards a Synthesized Critique of Neoliberal Biodiversity Conservation” Capitalism Nature Socialism 23, no. 2 (June 2012): 4-30. Doi: 10.1080/10455752.2012.674149

- Spash, Clive L. “Bulldozing biodiversity: The economics of offsets and trading-in Nature”. Biological Conservation 192 (December 2015): 541-551 .Doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.07.037

- Bockington, Dan and Rosaleen Duffy (eds.). Capitalism and Conservation. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Market ecocentrism:

- Wilson, E.O. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016.